In a survey we ran with our driver- and delivery-partners in 2021, the top two reasons selected by partners for why they choose to take up work via the Grab platform relate to the flexible nature of work (>70% selected “Flexibility of time”, >40% selected “Able to earn as much as I work”).1

But what does this flexibility really look like from a quantitative perspective?

The Public Affairs and Marketplace teams at Grab worked together to show with our data what flexibility looks like in the gig economy. The analysis illustrates the extent to which partners actually make use of the flexibility offered to them. We conducted this analysis using data from partners who were online for at least what would be considered “full-time” based on traditional employment definition – an average of at least 35 hours per week2 over a period of 10 weeks, to understand the difference between someone who does gig work “full-time”, versus an employee.

Data analysis

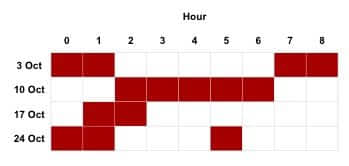

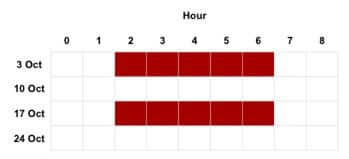

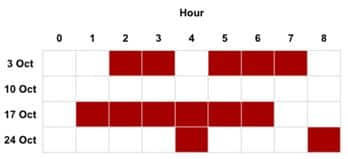

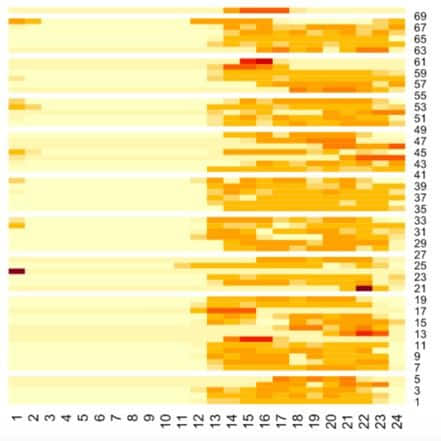

This is an illustration of what inconsistent work patterns look like when partners utilize the flexibility they have to decide when and how much they want to work:

Online daily, at inconsistent time slots:

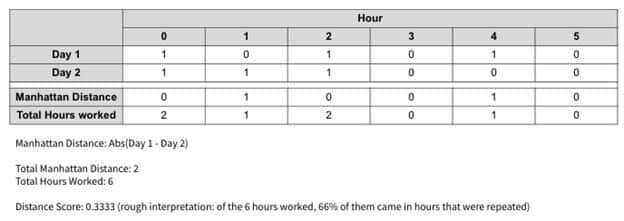

The extent to which an individual partner exhibits consistency in their working schedules can be quantified using the manhattan distance metric. The higher the number (between 0-1), the more inconsistent the partner’s working pattern:

The distance score represents the share of one’s working hours that are in different hour blocks. In the above example, the distance score is 0.33, which means that 33% of the hours worked are inconsistent.

We applied this analysis on a dataset of food delivery-partners on Grab Singapore’s platform who were online above what would be considered “full-time” hours – on average of at least 35 hours per week over a period of 10 weeks from 28 Dec 2020 to 7 Mar 2021.

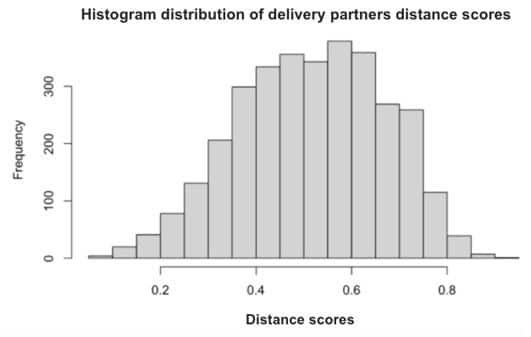

The data reveals that the median delivery partner had a distance score of 0.52, which means that ~52% of the hours online were inconsistent:

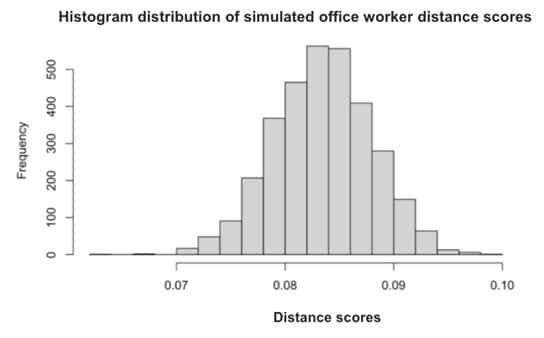

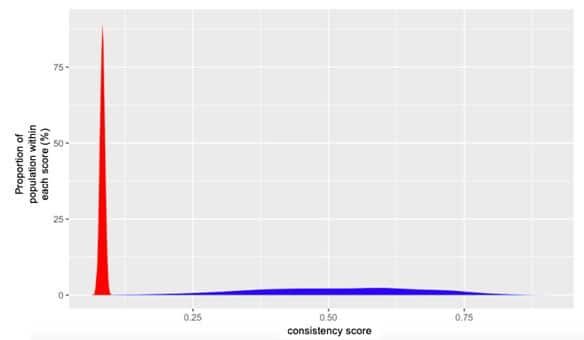

To understand how this compares with someone in a traditional job with a fixed work schedule, we ran a simulation of what this would look like for the hypothetical office worker, with the following assumptions:

- Office worker starts work from 9am to 6pm (1 hour lunch break), working 5 days a week (Monday to Friday), a total of 40 hours a week

- Office worker has 1 hour flexibility to start and end work (can do 8am to 5pm, 10am to 7pm or anything in between)

- Office worker has 1 hour flexibility for lunch break (can be 1 hour anytime between 12pm to 2pm)

The simulation shows that on average, office workers are likely to have a distance score of 0.08, which means that ~8% of the hours worked are inconsistent:

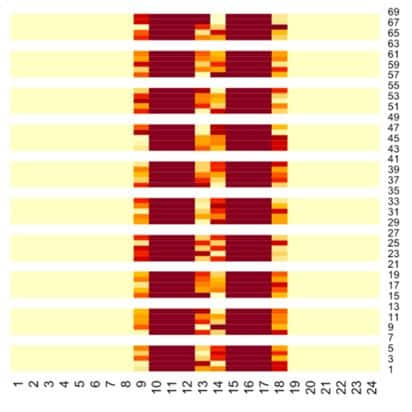

We replicated the graphical illustration of the work pattern of an “average” office worker in the 50th percentile:

Putting both populations together to compare the distribution of distance scores, it is clear that Grab Singapore’s delivery-partners who typically come online on what is considered a “full-time” basis have a highly inconsistent work pattern (area in blue in chart below), compared to office workers (area in red below):

The inconsistency also extends to the amount of time they come online over time. This is implicitly captured in the earlier analysis, but we want to bring to life what this means in relation to more traditional definitions of work commitment.

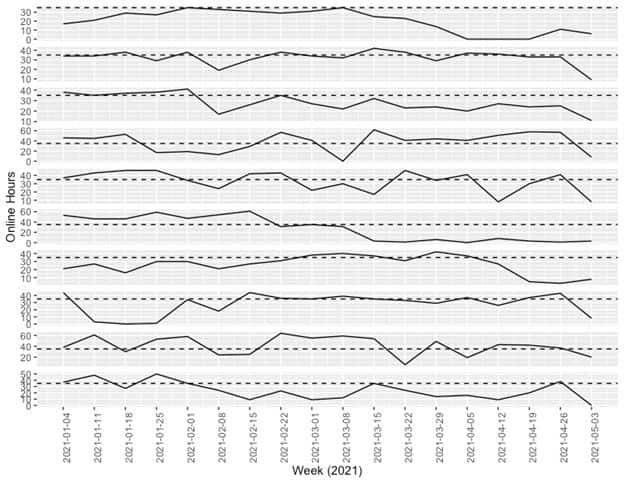

These are ten different delivery partners on the platform, with the number of hours they are online on the Grab app each week, since the start of 2021:

From the charts above, we can see that delivery partners easily move between being online for “full-time” hours (>35 hours per week), to “part-time” hours, to not even being online on the app at all, on a week to week basis. This illustrates the flexibility they have and take advantage of, which also makes it impractical to classify them as “full-time” or “part-time”, as these can change very quickly and frequently.

This is unique to gig work, as traditional employment is usually unable to accommodate such huge variations in commitment levels. It is a key part of the draw of “flexibility” that many who enter gig work talk about.

Implications on policy-making for the gig economy